The Friday Five is a weekly showcase of new Society6 artists. These talents come from all over the world, bringing fresh new styles and designs that deserve your attention. Find out more about today’s worldwide array of artists in their S6 stores. dellafiora (Nashville, Tennessee) weekender4014 (Yogyakarta, Indonesia) Luke Walzer (Mainz, Germany) almarrasquino (Mendoza, Argentina) Dan Hobday … Continued

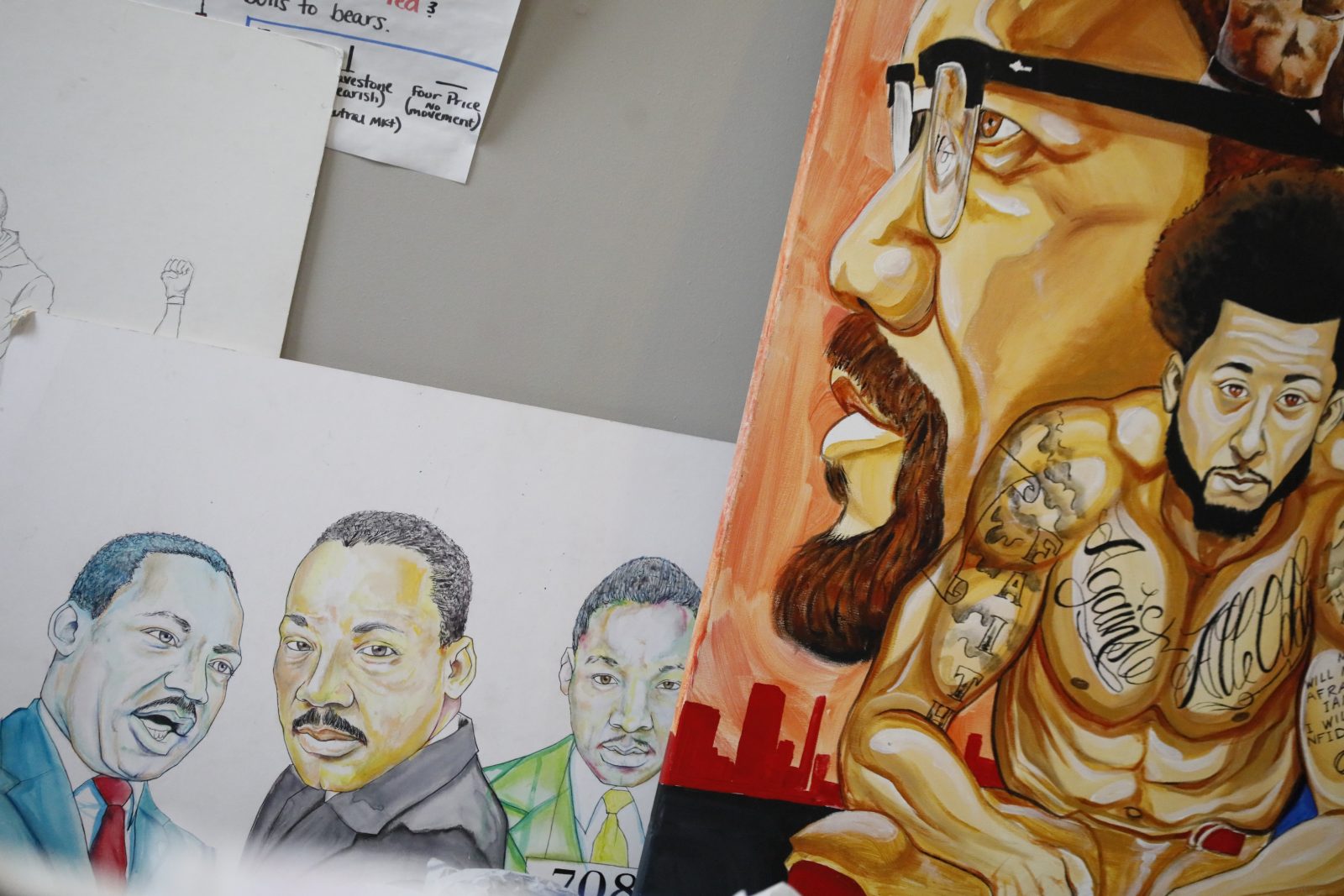

Aaron Maybin is an artist, an activist, an educator, an advocate, a poet, a photographer and a true champion for arts education in his hometown Baltimore community—and oh yeah, an All-American, first round NFL draft pick.

It should illustrate the importance of his multi-dimensional artistic voice as well as his work educating and advocating for kids throughout the Baltimore area to say that being the 11th overall pick in the 2009 NFL draft was really just another achievement on his increasingly long list. Here, we dig into Aaron’s life pre and post football, the role that arts played in his upbringing, and how he’s using the arts to make a real difference in the same Baltimore neighborhoods he grew up in.

On Discovering A Talent

Aaron’s artistic journey began “before he could even speak.” Creating gadgets and figurines out of aluminum foil, taking apart remotes and machines to create new projects—and then putting them all back together again. Aaron found that art (and eventually sports) was a space where he could really “lock in.”

“[Art] became my language. That became my method of expression. That became my first pursuit of mastery. And this is at like, 4 or 5 years old.”

And when Aaron was 6, art took on a whole new importance in his life as a tool for therapy after his mother tragically passed away while giving birth to his sister.

“Losing a parent at that age wasn’t just devastating, it was life shattering. It began my lifelong duel with anxiety and depression, so as a kid, I started to act out. Getting kicked out of schools, fighting, not paying attention and acting out of character for how I was raised to be.”

“Art served as my first exposure to therapy. Art was the first space that I was allowed to find my voice. Allowed to actually have a vehicle to talk about the pain and isolation I was feeling.”

Aaron goes on to explain how the presence of death in his childhood was nothing novel. His neighborhood in West Baltimore was of the lowest income, lowest education and remains one of the most segregated areas in the US to this day. Violence was part of his everyday life, with murder rates averaging over one per day in the city. However, he explains, what was different about his mother’s passing was that her death didn’t come from the streets. He says that dealing emotionally with his mother’s passing was obviously sorrow-filled and yet, in a sad way, an accomplishment—in that “the streets didn’t take her. That the streets didn’t make this person its dinner. It wasn’t a robbery or a murder or a rape or a kidnapping—it was natural causes.”

So it was at this point where arts education truly touched Aaron’s life as he began to spend more and more time with family friend, local artist and future mentor, Larry “Poncho” Brown.

On Developing A Passion

Poncho , as Aaron calls him, owned and operated a local arts studio from which he produced countless works of his own—earning placements for his art on TV shows like In Living Color and The Cosby Show. Poncho grew up with Aaron’s father and, at a time when Aaron struggled with behavioral issues, Aaron says, half-smirking:

“Poncho’s studio was the only place I could go without complaint. No one wanted to watch me.”

But Aaron goes on to say that his time at Poncho’s studio “was the most fun I ever had. Trailing him around, watching him work on everything at one time. It was honestly like a drug, I’d be chasing the high I would get from seeing him create.”

Beyond offering Aaron a place to hang and develop his talents, Poncho also opened a world of opportunities beyond the studio. He’d host annual city-wide art competitions for the kids to create art around certain topics and then provide the space for those same kids to showcase their work in a studio setting.

Aaron actually earned his first commissioned piece through one of Poncho’s art competitions, painting a mural for the city of Baltimore measuring 40 feet by 50 feet on the back of a Humanities building… at the age of 11!

“I’m so young that while I was up on the scaffolding painting this wall, we were at a corner with a red light next to one of those KFC and Taco Bell restaurants. There was a lot of traffic there, and so I would get confronted by people thinking I was a random kid from the neighborhood trying to deface this wall. And I’m like ‘No, I’m getting paid to paint this!’”

From there, Aaron continued under Poncho’s mentorship, winning competitions and at the age of 13, enrolling in college-level art courses on scholarship at the Maryland Institute College of Art. A feat that on its own should impress anyone, but takes on a whole new level when you consider that throughout this process, Aaron became one of the area’s top football recruits, eventually committing to play at NCAA powerhouse, Penn State.

In speaking with Aaron, you almost take for granted the dedication and overwhelming amount of work it took to balance a natural passion for art while also performing at the highest athletic levels. And it wasn’t until his time at Penn State that Aaron realized what a difference maker his football success on the field could become for his work off the field.

On Making A Difference

While attending Penn State, Aaron learned of budget cuts to the Baltimore public school system and immediately knew that the first programs to always hit the chopping block are the arts—programs that he admits “were already hanging on by a thread.” Recognizing that his upcoming NFL success would allow him a platform to make a difference, he founded Project Mayhem during his rookie year in 2009 as a response to the ever-waning public funding for Baltimore-area arts programs.

Hosting arts education seminars, annual celebrations for the arts and taking monthlong arts education tours to public schools without art programs, Aaron admits that while he did get a lot of pats on the back, his work “didn’t amount to anything. Because I’d go into these schools for a day or two, having these powerful conversations with the kids—but then I go back to my house and they go back to their house.”

“It was almost like a spit in the face because you expose them to this amazing thing. They’re saying, ‘Oh my God, this education exists and we can actually learn this way.’ And then they never get it again. I actually started getting depressed by that. Yeah, I was bringing awareness, but nothing is being done for the kids that actually need this educational programming.”

It forced Aaron to re-focus his efforts and leverage the access that an NFL career allows to meet and learn from political giants like Elijah Cummings, John Lewis and Louis Farrakhan. Aaron describes this period of time as his “indoctrination into real activism.” And as he left behind his NFL career, it was the lessons learned from those infamous activists that led Aaron back to Baltimore.

Joining Matthew Henson Elementary School as an arts educator, he was able to live and work in the communities he hoped to help. Developing curriculum used in 27 different schools across Baltimore, he is a true champion for “boots on the ground” activism. And it’s only the beginning of what he will accomplish.

To listen to Aaron speak is all the evidence you need to know how important the arts can be to kids and a community at large.

“Art is the soul within our lived experiences […] Art is what makes the world more flavorful, colorful, fun. […] Art is supposed to be therapy. It’s not supposed to be stressful. So have fun and allow it to give you something back.”

On Baltimore

“When people hear Baltimore, they think The Wire, the Ravens, crab cakes. But it’s important to shine a light on the other parts of the city.”

So I asked Aaron to help guide us to others in the community, who he stands alongside, making a real difference in the lives of kids and the city at large:

Brittany Young – Founder of B360 – B-360 has been on a mission to utilize dirt bike culture to end the cycle of poverty, disrupt the prison pipeline, and build bridges in communities

Erricka Bridgeford – Co-Organizer of Baltimore Cease Fire – The ultimate goal of Baltimore Ceasefire 365 is for everyone in the city to commit to zero murders. We are starting by calling ceasefire weekends, where we ask everyone to be peaceful and celebrate life.

D. Watkins – Author, Professor and Editor at Large for Salon Magazine

Artists

Photographers:

Devin Allen

Kyle Pompey

Kyle Yearwood

Kirby Griffin

Poets:

Jacob Mayberry (black chakra)

Slangston Hughes

Lady Brion

Nia June

Painters:

Monica Ikegwu

Megan Lewis

Ernest Shaw

Larry Poncho Brown

Davon Carey

Jerrell Gibbs

Brian Robinson

Writers:

D. Watkins

Kondwani Fidel

B sharice Moore

Curators:

Sharayna Christmas

Cheyenne Zadia

Photography for this piece by Kyle Pompey

Comments